The 2020 Australian ARF/RHD guideline: A behind the scenes look

Sara Noonan

Sara Noonan

RHDA Technical Advisor and Production Editor, 2020 Australian ARF/RHD guideline (3rd edition)

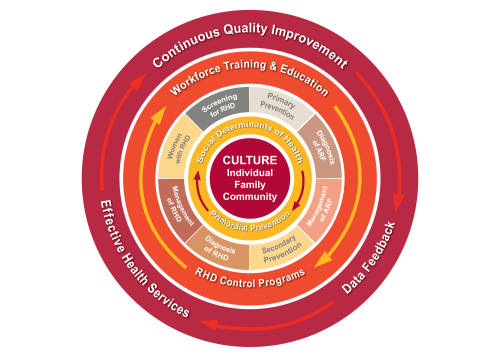

In February 2020, RHDAustralia released the third edition national guideline for acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD). It is packed with the most up-to-date evidence and insights for disease prevention, diagnosis and management, and for the first time it is underpinned by a socio-ecological model reflecting the complex and dynamic interrelations between people, clinical management, and the health system more broadly.

ARF and RHD have been the subject of increasing interest and activity in Australia since the mid-1990s, and I have been part of that journey.

My work with RHD started in 1997 after my return to Darwin from three years in the Marshall Islands. I worked with a small team to establish Australia’s first RHD control program at Darwin’s Centre for Disease Control. Priorities were centred around creating a disease register and offering education to the health workforce in line with the locally produced ARF/RHD protocol.

In response to a call from Australian clinicians for guidance to better inform the health workforce, Australia’s first national guideline was published by the Australian Heart Foundation and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand (CSANZ) in 2006. Participation in a writing group meeting in Melbourne in 2005 provided me with the opportunity to meet for the first time, many of the leading RHD researchers and clinicians I had heard and read about.

Around this time there was also growing concern among clinicians in several Pacific Island countries about the high burden of RHD in the region. Between 2005 and 2009, and drawing on my experience from the Top End, I provided technical advice and support to several Pacific Island countries through the World Heart Federation’s Pacific RHD Program. I worked with local governments of each country to determine their priorities and capacity for RHD control, and some countries adopted relevant elements of the 2006 Australian guideline into their local ARF/RHD protocols.

In 2009, Australia’s National RHD Coordination Unit, RHDAustralia, was established as part of Australia’s Rheumatic Fever Strategy. RHDAustralia’s role was to oversee development of a national model of best practice for registers, education and training, and clinical practice. Funding was independently provided to several jurisdictions to establish or strengthen RHD programs. In my role as RHDA technical advisor I supported the programs, facilitated workshops, and consulted with the RHD programs, epidemiologists and data specialists to develop benchmarks for national ARF/RHD data collection and reporting.

To maintain national guidance in line with emerging evidence, in 2012 RHDAustralia published an updated second guideline edition in partnership with the Australian Heart Foundation and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand (CSANZ). My role was to coordinate this review, which included a new chapter; extending beyond just the clinical, highlighting primordial and primary prevention of ARF and social determinants of disease.

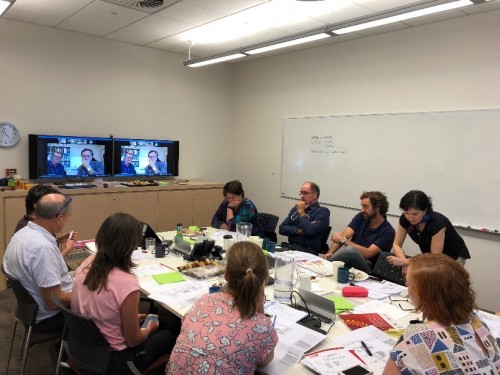

I subsequently returned to RHDA as Technical Advisor and Production Editor for the 3rd Edition of the guidelines. We first conducted a review of the second edition during 2018 and 2019. This time, it was important to have input from a range of people and disciplines to ensure that the information would be not only clinically sound, but also practical, relevant, and delivered in a way that busy people can understand. Contributors to the 2020 guideline included nurses and midwives, Aboriginal Health Workers, cardiothoracic surgeons, allied health professionals, remote area nurses and GPs, paediatricians and physicians, qualitative researchers, cardiologists, epidemiologists, Aboriginal Liaison Officers, dentists, pharmacists, primary care staff, cardiac sonographers, RHD Program staff, obstetricians, and peak body representatives including the Heart Foundation, the CSANZ and others. Several people working in rural and remote areas kindly worked through some of the clinical pathways for clarity and applicability. The goal was to achieve the broadest base of category contribution that we could access.

A guideline steering committee was established to oversee the quality of information and guide the review process. A meeting of the steering committee and chapter lead authors was hosted from Darwin in May 2019. This gave us an opportunity to review capacity and expertise within the writing groups, identify gaps in content, and agree on a timeline for delivering chapters for review. There was robust discussion around definition of risk groups, recommended duration of secondary prophylaxis, and follow-up and management planning. These key areas received a lot of attention and have been updated significantly.

Some other recommendations have been updated to align with other guidelines; for example, the criteria for ARF diagnosis (page 74) now aligns with the 2015 American Heart Association recommendations, and the cardiac conditions and procedures indicated for endocarditis prevention (page 223) are modified from the 2019 Australian Therapeutic Guidelines .

Format and presentation were largely shaped by feedback from a national health workforce survey conducted in 2018. Key information is presented separately and at the front of each chapter, and tables, photos and clinical pathways have been included. Links to additional web-based information including videos and publications are threaded throughout the document, to help cater to the tech-savvy health workforce.

The reader may notice that some of the important information in the guideline has been pushed further forward and highlighted in blue boxes throughout the text. The authors felt this was important because while the guideline is packed with lots of important messages, there are some specific elements of care that can have a significant impact on patient outcomes. For example, a blue box on page 76 stresses the importance of hospital admission for all people suspected with ARF, and two boxes on page 171 include important considerations for ceasing secondary prophylaxis that provide much greater clarity for clinicians and should enable earlier cessation of secondary prophylaxis in quite a few people.

An underpinning cultural framework has been included in the 2020 guideline to help describe how care can be both clinically sound and culturally safe. In this model, the individual is central, surrounded by culture, family and the wider community. This has a direct influence on how quality evidence-based care is received and adopted. If care is to be effective, it is vital that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, who are disproportionately affected by ARF and RHD, have a strong voice in how treatment is delivered. Through the guideline we attempt to bring this voice forward.

A Cultural/Workforce Advisory Group, led by Vicki Wade, reviewed every chapter to identify opportunities where the cultural considerations for care should be highlighted. Culture and workforce are highlighted in orange boxes. For example, the orange boxes on page 65 and 126 alert the reader to the importance of culturally appropriate education for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients. Boxes on pages 30 and 276 highlight the importance of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce, which is uniquely placed to help translate clinical care into culturally appropriate practice.

Peoples’ stories have also been included throughout the guideline as a series of quotes and case studies to help highlight the personal burden of ARF and RHD, which can get buried under the robust agenda of diagnosis and management. Sam’s story on page 97 is an example of one boy’s resilience following a delayed diagnosis of ARF, and case studies starting on page 265 highlight elements of care for four pregnant women with RHD. The Murdi Paaki Healthy Housing Worker Program described on page 50 is an example of strength in communities around healthy infrastructure and disease prevention.

One of the biggest challenges has been to maintain robust guidance for eliminating this disease, while not setting impossible goals for the Australian health system. While it was sometimes difficult to find this balance, I believe we have established a high-quality evidence-based standard for care that our population deserves, and I hope that recommendations can be used to help drive system change to improve service wherever needed.

On a personal basis, my professional networks have continued to expand through my technical work and through various research projects in which I have been involved in Australia and overseas. For many years I have had the privilege of working with lots of skilled people who are dedicated to improving care and reducing ARF and RHD, and I am always grateful that I can contact them and know that an answer will be given, consultation will be had, and an expert consensus reached.

I believe that such open and honest collaboration has resulted in a guideline that is well-considered and very well-intended. I am very excited about the release of this guideline, and I believe that a new bar has been set for medical guidelines that support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health in Australia.