The latest figures for acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia, a snapshot.

Prepared by Sara Noonan

RHDAustralia acknowledges that the figures presented in this article are not just numbers on the page but represent many stories of suffering, uncertainty, and loss in communities around Australia.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare's report Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia, 2016–2020.1 provides an epidemiological overview of acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD) from registers located in Western Australia, South Australia, Queensland, New South Wales, and the Northern Territory.

The results provide compelling evidence for the need to improve environmental conditions to manage Strep A infections and reduce ARF and RHD. The increasing number of people diagnosed with RHD highlights the urgent and important need for improved and sustained ARF awareness and identification through a multisector approach.

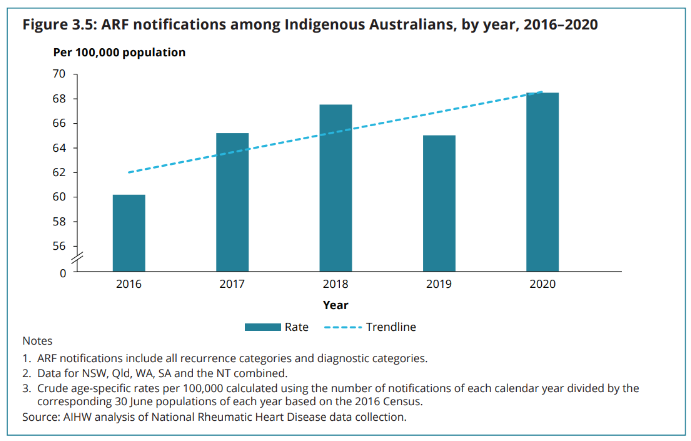

In Australia between 2016 and 2020, the number and rate of ARF notifications increased, with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples accounting for 92% of cases. Of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on the registers:

- the rate of ARF notifications increased from 60 per 100,000 in 2016 to 69 per 100,000 in 2020. (Figure 3.5 below, AIHW 2022)

- the rate of ARF recurrence among people prescribed regular benzathine benzylpenicillin G (BPG) injections decreased.

- the rate of new RHD diagnoses increased.

- 80% of people newly diagnosed with RHD did not have a previous diagnosis of ARF recorded.

- 14% of people had severe RHD at the time of their diagnosis.

- overall, the doses of BPG administered as a proportion of the doses required, has not improved.

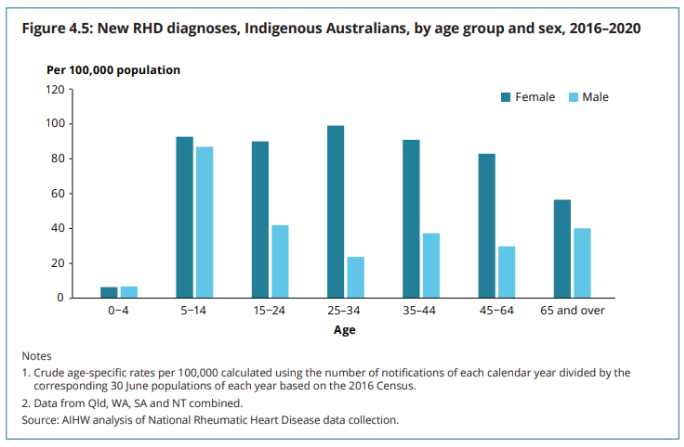

Of the ARF diagnoses between 2016 and 2020, almost half (46%) were children aged 5-14 years. ARF rates in children aged under 15 years were generally higher among males, and in adults, ARF rates were generally higher among females. 27% of all ARF diagnoses were recurrences.

The median age at RHD diagnosis was 23 years, and females had higher rates for RHD in all age groups, excluding 0-4 years (Figure 4.5 below, AIHW 2022).

In 2020 there were more than 9,000 individuals living with a diagnosis of ARF and/or RHD recorded on Australian state and territory registers. While the burden of ARF and RHD among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities is well-known and extensively published, cases are also found among other groups such as Māori, Pacific Islanders and migrants from countries where ARF and RHD are common.

For example, while numbers on the New South Wales register are relatively small (163 people, compared to more than 3,000 each in Queendland and the Northern Territory), the population on the New South Wales register is diverse. There were more RHD diagnoses among non-Indigenous Australians than among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians during the latest report period, and Māori and Pacific Islander peoples accounted for 29% of all new RHD diagnoses.

While there have been informal reports from some communities highlighting improved and sustained success with regular BPG injection delivery, overall, the AIHW found that injection delivery did not improve between 2016 to 2020. Of the more than 4,500 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in need of these injections (excluding NSW), 36% received less than 50% of the required doses, which leaves individuals at high risk for recurrent ARF.

The AIHW reports do not include information about the burden of Strep A infections which cause ARF, because this is outside the scope of the ARF/RHD registers. Individual reports for each state/territory will be released in mid-August 2022.

For more information, download the full 2016-2020 report from the AIHW website.

- 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2022). Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia 2016–2020, catalogue number CVD 95, AIHW, Australian Government