Clinical Update - Primary Prevention of ARF

The 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease (3rd edition) contains clinical information based on national and international best practice. The information is supported by a cultural framework to highlight the importance of how care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD) should be both clinically sound, and culturally safe.

There are several opportunities for intervention - prevention along the ARF-RHD disease pathway including primordial prevention of group A streptococcal (Strep A) infections, primary prevention of ARF, secondary prevention of ARF, and tertiary prevention of complications associated with RHD. In this article, we take a closer look at primary prevention.

Strep A Infections and Primary Prevention Of ARF

Primary prevention of ARF aims to interrupt the link between the Strep A infection and the abnormal immune response to the infection that causes ARF. This is achieved by identifying and treating Strep A infections early.

In Australia, recommendations for primary prevention are based on an individual’s level of risk for ARF. Some groups are at high risk for ARF,1 and people in these groups should receive antibiotic treatment immediately; after a personal and medical history, clinical assessment, and swab for Strep A have been taken. These people are:

- People living in an ARF-endemic setting†

- Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples living in rural or remote settings

- Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples, and Māori and/or Pacific Islander peoples living in metropolitan households affected by crowding and/or lower socioeconomic status

- People who have had ARF/RHD and are aged less than 40 years.

†This refers to populations where community ARF/RHD rates are known to be high e.g. ARF incidence >30/100,000 per year in 5–14-year-olds or RHD all-age prevalence >2/1000.

Transmission of Strep A from person to person is increased when there is household crowding, especially when poorly maintained housing conditions make hygiene difficult. Strep A is especially shared around households where there are children with respiratory infections and skin conditions such as skin sores, scabies and head lice.

Infections of the throat and skin have been associated with ARF.

Throat Infections

Photo courtesy of Associate Professor Asha Bowen.

Photo courtesy of Associate Professor Asha Bowen.

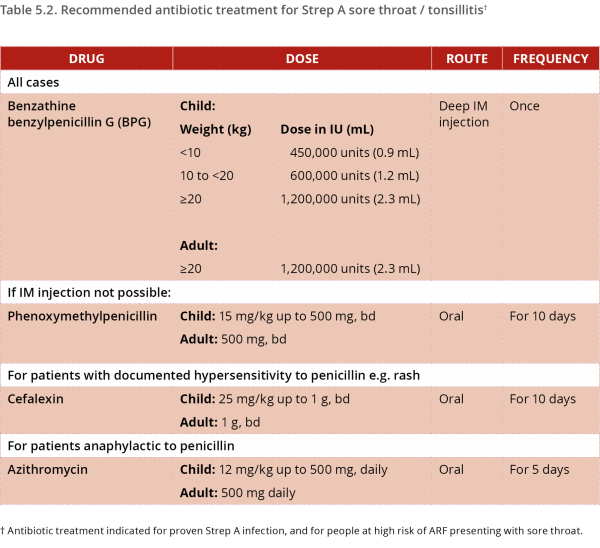

Strep A is only one cause of sore throat and tonsillitis, and is present in 10% to 40% of children with a sore throat.2 The remainder of throat infections are caused by viruses, or by other microbes. Treating throat infections caused by Strep A can decrease the subsequent development of ARF by up to two-thirds.3

Symptoms and signs of Strep A throat infection can include pain and difficulty swallowing, croaky voice, fever, enlarged tonsils which may be covered in exudate, enlarged cervical lymph nodes, and reluctance to eat and drink (due to the discomfort).

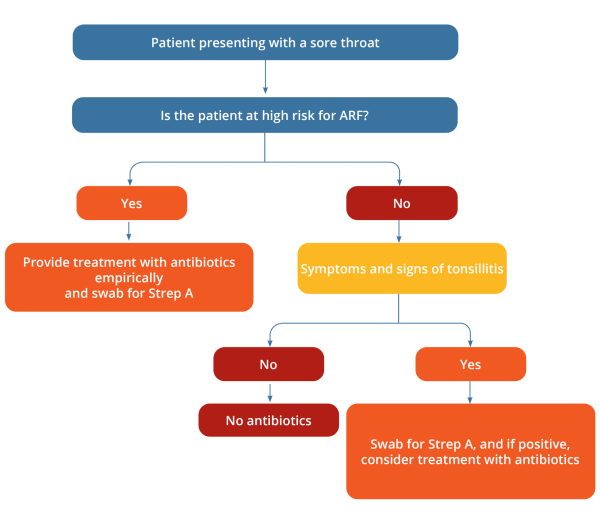

The following pathway can assist clinicians to assess sore throats based on the individual’s level of risk for ARF, and their presenting symptoms and signs.1

Guidelines often caution against the overuse of antibiotics for sore throats, however, due to the high impact resulting from ARF and RHD, people who are at increased risk of developing ARF should be treated with antibiotics if they develop a sore throat, irrespective of other clinical features.

| Knowing when to treat sore throats with antibiotics to prevent ARF is an important learning point for all health staff working with populations at high risk of ARF. |

Skin Infections

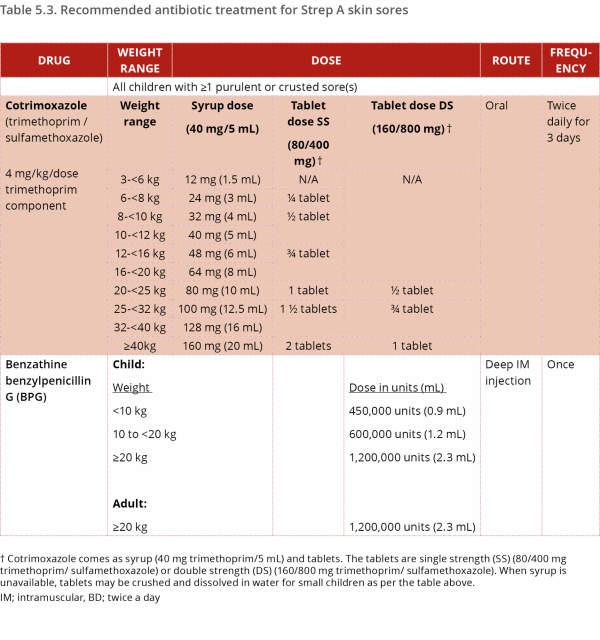

Strep A skin infections include skin sores and impetigo. Strep A has been shown to be associated with up to 82% of impetigo episodes,4,5 which is a very common condition among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children living in remote areas.6 Strep A skin sores are often round or linear, 1-2 cm in size and have pus or a thick crust evident.

Photos courtesy of Associate Professor Asha Bowen

Cotrimoxazole and benzathine benzylpenicillin have been compared in a randomised controlled trial in Australian Aboriginal children with skin sores. A three-day course of twice-daily or a five-day course of once-daily cotrimoxazole were found to be of similar effectiveness to benzathine benzylpenicillin for the treatment of skin sores.7 Cotrimoxazole had significantly fewer side effects, was well tolerated, and provided a pain-free alternative to the injection.

High risk individuals who are already receiving regular benzathine benzylpenicillin injections for ARF still need treatment for sore throats and skin sores. This is necessary because the level of benzathine benzylpenicillin decreases at around day 7 to reach a prevention level, which is lower than the treatment level required for the Strep A infection. For example:

- If the last regular benzathine benzylpenicillin injection was given 7 or more days before a sore throat, an additional injection* should be given. The date of the next regular injection is then reset to 21-28 days after this injection.

- If the last regular benzathine benzylpenicillin injection was given 7 or more days before skin sores, cotrimoxazole (first line) or an additional benzathine benzylpenicillin injection* should be given. If the injection is given, the date of the next regular injection is reset to 21-28 days after this injection.

Treatment options for skin sores should be discussed with children’s parents or carers so that they can be involved in deciding the best treatment for their child on each occasion.8

|

* Benzathine benzylpenicillin injection regimens for primary treatment and secondary prevention differ in frequency, but not in weight-based dosing. To make it easier to remember secondary prophylaxis dosing, which is almost never needed for children weighing less than 10kg unlike primary prevention, the guidelines merge the <20kg weight categories for this indication:

|

Updated recommendations for primary prevention of ARF will inform other guidelines as they are updated. For more information about primary prevention of ARF, refer to the 2020 Australian guideline (pages 56-69).

References

- RHDAustralia (ARF/RHD writing group). The 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease (3rd edition); 2020.

- Oliver J, Malliya Wadu E, Pierse N, et al. Group A Streptococcus pharyngitis and pharyngeal carriage: A meta-analysis. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2018;12(3):e0006335.

- Spinks A, Glasziou PP, Del Mar C B. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013;(11):CD000023.

- McDonald M, Towers RJ, Andrews RM, et al. Low rates of streptococcal pharyngitis and high rates of pyoderma in Australian Aboriginal communities where acute rheumatic fever is hyperendemic. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2006;43(6):683-689.

- Carapetis J, Connors C, Yarmirr D, et al. Success of a scabies control program in an Australian Aboriginal community. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 1997;16:494-499.

- Bowen AC, Mahé A, Hay RJ, et al. The Global Epidemiology of Impetigo: A Systematic Review of the Population Prevalence of Impetigo and Pyoderma. PLOS One 2015;10(8):e0136789.

- Bowen AC, Tong SYC, Andrews RM, et al. Short-course oral co-trimoxazole versus intramuscular benzathine benzylpenicillin for impetigo in a highly endemic region: an open-label, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. The Lancet 2014;384(9960):2132-2140

- Amgarth-Duff I, Hendrickx D, Bowen A, et al. Talking skin: attitudes and practices around skin infections, treatment options, and their clinical management in a remote region in Western Australia. Rural and Remote Health, 2019.